- Home

- T1-1 PARTICIPANT LIST FOR ONE HEALTH MALAWI

- T2 COHESA One Health Malawi Summary List

- T3 Malawi One Health Baseline Report Version 1 19042023

T3 Malawi One Health Baseline Report Version 1 - 19042023 - Catherine Wood

T3 Malawi One Health Baseline Report Version 1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Context

- Environmental Health

- Human Health

- Animal Health

Research and Innovation

Governance

- Background

- National policies, plans, and strategies specific to One Health

- National policies, plans, and strategies relevant to One Health

- Actors in One Health Governance

- Funding Mechanisms

- Overall Strengths in One Health Governance

- Gaps in One Health Governance

Education

- One Health education in primary schools

- One Health education in secondary schools

- One Health education in universities

- Strengths in One Health Education

- Gaps in One Health education

Implementation of One Health Activities and Initiatives in Malawi

- Initiative Gaps

Reflection on the Desktop Review

Monitoring and Evaluation

- Incidence of focal OH disease

- > Zoonotic diseases – human data

- > Zoonotic Disease – animal data

- > Foodborne diseases

- Agrochemical and Pharmaceutical Data

- > Number of OH strategies and policies by sector

- > Current number of OH initiatives

- > Operational OH platform in country

References

- Government Documents and Reports

- Journal Articles

- News Articles

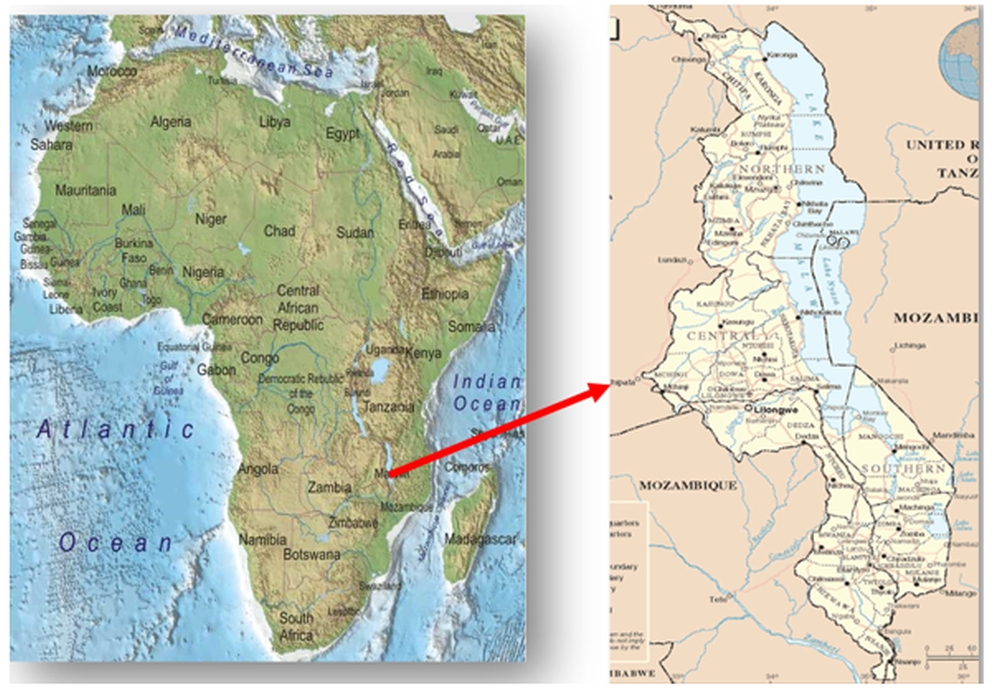

CONTEXT

Malawi is a densely populated, land-locked country in southern Africa, with a primarily agrarian economy. In recent decades, Malawi has experienced slow, erratic economic growth and high levels of poverty remain unchanged, with a per capita GNI of US$320 in 2017. The agricultural sector generates almost 30 percent of GDP and the majority of total exports; over 80 percent of households depend on agriculture for some income with the majority of the population practicing subsistence agriculture. There is growing concern about food and income security, largely as a result of rapid human population growth, weak infrastructure, and climate shocks but also as a result of macroeconomic instability. Malawi’s human population also suffers high levels of endemic infectious diseases such as malaria, HIV, and cholera and also from chronic and acute malnutrition (World Bank Group 2018; FAO 2020).

Furthermore, degradation of the environment, including soil infertility, compromised water quality, over fishing, and loss of wild habitat and biodiversity secondary to human population pressures need to be addressed in parallel.

This review examines research and innovation, governance, education, and implementation of One Health in Malawi.

Environmental Health

Malawi has a diverse ecosystem consisting of forest, semi-arid planes, and wetland habitats and a large inland lake. There are many threats to environmental health and biodiversity including habitat loss and fragmentation, over fishing, overgrazing, bushmeat trade and wildlife trafficking, pollution of water, land, and air; introduction of invasive species, other pests, and pathogens; and deforestation largely due to harvesting of wood and charcoal for cooking. The FAO estimates Malawi has lost 19 percent of forest cover over the past 25 years, and the rate of accelerating soil erosion is severe and worsening, and groundwater levels are dropping. Malawi has no properly constructed landfills and most districts do not have sewage systems (Malawi National Environmental Health Policy 2010, Global Forests Resources Assessment 2020).

Human population pressure is the primary driver of environmental degradation. Human population pressure also makes farming very challenging, with the average farmer having less than 1.0 ha, which precludes cultivation of pasture crops for livestock and constrains crop diversification. Demand for agricultural land has resulted in encroachment into forest reserves and national parks (FAO 2022, Country Pasture/ Forages Resource Profile 2006).

Malawi is also particularly vulnerable to climate change. In recent years, Malawi has experienced severe weather events such as the the El-Niño-induced drought of 2016 and flooding in the Southern Region in 2015 and again in 2021. In January of 2022, heavy rainfall in the face of severe erosion caused the Shire River to change course overnight, rendering the country’s main hydroelectric plant, Kapichira, non-functional. Malawi’s crop agriculture sector, which is 49% maize and almost entirely rain fed, is very sensitive to such climate shocks. Climate change in Malawi is also predicted to expand the geographical range of vector-borne illness (IFRC 2021).

Human Health

In Malawi, the primary human health concerns are malnutrition/under-nutrition and infectious disease.

Top Ten Causes of Deaths in Malawi according to Bowie (2011).

- HIV/AIDS 25 %

- Lower respiratory infections 12 %

- Diarrheal diseases 8 % (Currently, Malawi is battling a cholera outbreak.)

- Malaria 8%

- Cerebrovascular disease 4 %

- Ischaemic heart disease 4 %

- Conditions arising during perinatal period 3 %

- Tuberculosis 3 %

- Road traffic accidents 2%

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary 1%

Emerging zoonotic diseases of concern include middle east respiratory syndrome, avian and other influenza viruses, and sudden acute respiratory syndrome/COVID. Neglected zoonotic diseases of concern include anthrax, trypanosomiasis, Brucellosis, rabies, cysticercosis, and bovine tuberculosis. The transmission of drug-resistant pathogens among humans and from livestock to humans is another health concern as is mycotoxin contamination of maize. Malnutrition in Malawi, particularly micronutrient deficiencies, is common as a result of lack of diversity of agricultural products available for consumption and from farming said products on mineral-depleted soil. (WHO 2022, WHO 2021, Warnatzsch et al 2020).

Most Malawians are aware of COVID-19 policies and messages, and they are taking steps to limit their exposure to the virus. COVID-19 has caused food insecurity and price increases; the government must increase the availability of food and agricultural inputs in rural areas and support livelihoods and social protection package design and interventions with evidence-based policy-making (Ambler et al 2022)

Animal Health

Livestock production in Malawi faces a number of challenges, including limited pasture due to population pressure, inadequate feed production and storage technologies, and insufficient animal health support infrastructure and services. Like the human population, main challenges to domestic animal health are infectious disease and under nutrition (Malawi National Livestock Development Policy 2021, Malawi National Agricultural Policy 2016).

Over fishing in Malawi is severe, particularly along lake shores and in shallow water bodies. This is partly due to weak legislation and enforcement; insufficient production and access to quality fingerlings and feed for aquaculture; and underutilized deep water fish resources. In addition, there is low access to capital for investment in fish farming and limited availability of improved fishing technologies (Malawi National Fisheries and Aquaculture Policy 2016, Limuwa et al 2018).

Malawi’s wildlife populations have been decimated in recent decades due to habitat destruction and poaching. In 2016, Malawi was identified as a hotspot for wildlife crimes aggravated by poor enforcement and weak legislation. There have been positive developments in recent years, with Liwonde and Majete National Park flourishing under the management of African Parks and the government of Malawi, in partnership with the Lilongwe Wildlife Trust, establishing and enforcing strict penalties for wildlife crimes (Waterland et al 2015, Kumchedwa 2018).

RESEARCH AND INNOVATION

Publications on research related to One Health in Malawi over the past 5 years are referenced and further detailed in Appendix 1. https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1JkdE6paiUF1xapP_mcJaMOOk5Y_T2ZjpazOH0TFOK1I/edit?usp=sharing

The individual papers are available in

https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1zkjyc-FeuhTzp75s0-mQfy3UVufG005u?usp=share_link

LITERATURE REVIEW FOR ONE HEALTH RELATED WORK IN MALAWI

AMR research

Most of research work on Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in Malawi has been done in the human health sector by human health experts from the Kamuzu University of Health Sciences (formerly known as the Malawi College of Medicine) and the Malawi Liverpool Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Program together with different international collaborators from different universities: University of Liverpool, University of Edinburgh, University College London, John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Macquarie University, Osaka university and Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine just to mention a few. Research in the human health sector has focused on understanding the emergence of AMR in different species of bacteria to antibiotics (Phiri et al., 2021; Stenhouse et al., 2021; Tam et al., 2019); understanding antimicrobial use (AMU) in different demographic settings and its implications on public awareness (MacPherson et al., 2022); knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to AMR and AMU(MacPherson et al., 2021; Sambakunsi et al., 2019) ; evaluation of the impact of vaccines on AMR (Swarthout, 2020); genomic epidemiology of important bacteria species (Tegha et al., 2021); genomic analysis of AMR associated pathogens (Lewis et al., 2022; Musicha et al., 2019); and novel methods for extraction of antimicrobial resistance genes in the environment (Byrne et al., 2022). However, the role and growing impact of animal and environmental reservoirs of resistance is not usually explicitly considered in the design and implementation of research as observed by apparent lack of multisectoral collaborations in AMR research.

Evidence of resistance to antimicrobials in humans has been found in different species of bacteria including Salmonella and E. coli spp., fluoroquinolone resistant Shigella species (Stenhouse et al., 2021), ampicillin, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, sulfonamide resistant Shigella species (Phiri et al., 2021), and antibiotic resistant Klebsiella spp. (Tam et al., 2019). Genomic epidemiology studies have also suggested an increase in the distribution of antibiotic resistant genes in the country (Tegha et al., 2021). Emergence of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae has also been reported in Malawi (Lewis et al., 2020). Genomic analysis of Klebsiella pneumoniae (KPN) isolates from humans has also revealed the presence of multiple Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBL) genes across diverse KPN lineages in Malawi and plasmids that are in circulation can carry carbapenem resistance (Musicha et al., 2019). As such, there is need to quickly intervene to avoid a high burden of locally untreatable infection that are likely to occur in vulnerable populations. (Byrne et al., 2022) evaluated a novel, magnetic bead-based method for the isolation of antimicrobial resistance genes (ARG) from river water named MagnaExtract (a low-cost extraction method independent of commercial kits or reagents). It was found that the MagnaExtract method is comparable, and in some instances superior to commercially available kits for the isolation of ARGs from river water samples. On public awareness of AMR, it has been argued that as much as public AMR awareness is an important effort in the fight against AMR, strengthening primary health care systems is very critical in the fight, especially in low and middle income countries (LMIC) where access to health care systems is a challenge (MacPherson et al., 2021, 2022). Sambakunsi et al., (2019) also reported that self-medication is a public health risk that needs to be addressed urgently.

Generally, information on AMR research in animals and the environment is scant. However, some unpublished work has been able to characterize AMR in livestock. A University of California Davis global programs funded pilot study which was conducted by a One Health fellow from the institution in 2021 characterized AMR of E. coli in commercial and village poultry in Lilongwe district and showed evidence of AMR in E.coli. The prevalence of resistance was higher in broilers than village chickens which was attributed to the fact that broilers are usually raised under intensive management systems where antibiotics are heavily used, while antibiotic use in village chickens, which are usually raised under extensive management system, is minimal. High AMR prevalence in sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, tetracycline, ampicillin, and partly ciprofloxacin was reported, and this suggested their common use in the poultry sector in Malawi. Generally, this evidence concurred with evidence that was generated from a similar surveillance in Malawi poultry that was implemented by the Department of Animal Health and Livestock Development and University of North Carolina under the Fleming fund project. An unpublished student research by a final year veterinary medicine student at Lilongwe University of Agriculture and Natural Resources also found evidence of AMR in E. Coli isolated from livestock (cattle, chickens, goats, and pigs) and humans.

Rabies research

Some of the key focus areas on rabies research in Malawi include mass canine rabies vaccination and its impacts on human health, innovations for data collection and management, approaches to increase vaccination coverage and herd immunity, and estimation of ownerless and free-roaming dog populations. Institutions that have played a key role in rabies research in Malawi include Department of Animal Health and Livestock Development, Mission rabies, Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital, Worldwide Veterinary Services, and the University of Edinburgh. Studies have indicated that

1) canine rabies vaccination is important in elimination of rabies in humans,

2) a combination of temporary static clinics with follow up door-to-door vaccination teams can increase vaccination coverage,

3) private rabies vaccination is influenced by sociodemographic factors,

4) data-driven approaches can improve delivery of animal health care interventions for public health.

Adoption of One Health approaches and intersectoral collaboration in rabies research was demonstrated in a retrospective study that was conducted by shimmer et al 2018 (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2018.11.165) to determine the impact of a comprehensive canine vaccine campaign on paediatric rabies cases at Queens Elizabeth Central Hospital in Blantyre, Malawi. The main finding in this study was that canine rabies vaccination programs could help to reduce paediatric rabies cases and prevent unnecessary child death.

Bovine Tuberculosis (bTB)

Generally, little has been done on bTB in Malawi. Much as it is widely recognized to be a zoonotic disease of public importance, minimal research work, mostly focusing on livestock has been done. From the little work done, an explicit emphasis on the importance of using one health approaches in bTB research is not evident. In Malawi, bTB studies have mainly focused on understanding the prevalence and risk factors (Flav Kapalamula et al., n.d.) and its molecular epidemiology (Kapalamula et al., 2022). Considering its significant public health importance, it is important to implement one health approaches in bTB research.

Schistosomiasis

Schistosomiasis research and interventions in Malawi have mainly focused on surveillance activities and control interventions focusing on health education, improved water supply, sanitation, and mass chemotherapy. Most of the work has been done by human health experts with little to zero collaboration with animal and environmental health counterparts. A study done by researchers from the Malawi Liverpool Wellcome Trust showed that human schistosomes have the potential for abrupt changes in their genetic constitution through genetic interactions with schistosomes in livestock. This entails that as efforts to eliminate schistosomiasis as a public health problem and interrupt transmission gather momentum, it is important to employ one health approaches in order to effectively control the disease. In a study done by Richard Stauffer & Madsen (2018), it was concluded that a One Health approach must be employed to effectively control urinary schistosomiasis in Lake Malawi. Kayuni et al. (2020) recommended stepped-up preventive chemotherapy, with increased community-access to treatments, alongside renewed efforts in appropriate environmental control.

Trypanosomiasis

Human African trypanosomosis, often referred to as “sleeping sickness”, is a neglected tropical disease that occurs in Malawi (Chimera et al., 2021). In Malawi, the principle determinant of tsetse distribution is the expansion of human settlements and gradual encroachment on wildlife areas. The expansion of human settlements and the clearing of vegetation for cultivation lead to interactions among tsetse, cattle, wildlife, and humans. Human trypanosome infections are subsequently endemic in areas adjacent to game reserves and forests (Chisi et al., 2011). Both wildlife and livestock can be infected with human pathogenic trypanosomes. In Malawi, research has focused on understanding the epidemiology of this vector borne disease in livestock and humans separately. However, some studies have investigated pathogenic trypanosomes in a One Health context. For example, a study conducted by Chimera et al., 2021, who did a One Health investigation among livestock farmers and livestock in a cross-sectional survey concluded that the control of zoonotic diseases that impact poor livestock herders requires a One Health approach due to the close contact between humans and their animals and the reliance on animal production for a sustainable livelihood.

Researchers from the KUHES also collaborated with other researchers from Hokkaido University, Institute of Tropical Medicine (Antwerp, Belgium), Levy Mwanawasa Medical university and the University of Zambia to develop a bio-inkjet printed LAMP test kit for detecting human African trypanosomiasis (Hayashida et al., 2020).

Climate change and wildlife

Over the past years, a lot of modelling work and qualitative research has been done to quantify and qualify the impact of climate change on human health, animal health, food systems, nutrition, and food security. In the context of human and animal health, growing research has mainly concentrated on understanding the impact of climate change on infectious diseases through integration of climatic and non-climatic data into routine infectious diseases data (Chirombo et al., 2020); climatic impacts on food systems and adaptation measures (Limuwa et al., 2018; Muchuru & Nhamo, 2019); climatic influences on the risk of seasonal bloodstream diseases such as typhoid and invasive non-typhoid Salmonella (Thindwa et al., 2019); impact of climate change on aflatoxin contamination in crops (Warnatzsch et al., 2020); climate change, migration and associated health impacts; and the health impacts of climate change on smallholder farmers in terms of communicable and non-communicable diseases, mental health and occupation health, safety and other health issues (Talukder et al., 2021).

Wildlife research has focused on areas such as poaching and its impacts, sustainable natural resource management, wildlife diseases (such as epizootic ulcerative syndrome in fish and anthrax in Hippos). It is also worth noting that on some rare occasions, animal health experts work in collaboration with environmental and human health experts to investigate diseases of wild animals that are zoonotic – a case of anthrax outbreak in 2018 at Liwonde national park. However, more still needs to be done to enhance collaboration and coordination amongst stakeholders in wildlife related research.

Covid-19

Covid-19 research in Malawi has focused mask disposal behaviors; spatial and temporal risk modelling; knowledge, beliefs, perceptions, behaviors, and practices associated with covid-19; incidence, prevalence, and immunity; socio-economic impacts; implications of covid-19 on agriculture, nutrition, and food security; policy responses; and covid-19 response in the wake of various religious and traditional beliefs.

Water quality

Research on water quality has focused on wastewater management; analysis of water samples obtained from the formal and informal food outlets for the presence of faecal coliforms that are indicative of poor sanitation that result in foodborne infections amongst consumers; and shoreline water quality assessment just to mention some.

Environment and landscape

On the environmental theme, areas of research focus include data management and utilization; understanding effects of different environmental contaminants on human health; deforestation, food security and deforestation; assessment of different water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) interventions in the wake of different infectious disease outbreaks such as typhoid fever and cholera; pesticide exposure management; soil health and biodiversity research.

Other zoonoses

Epidemiological studies have also been conducted on Rift Valley fever, Bovine brucellosis, Taenia saginata taeniosis/cysticercosis, and Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever. However, more work still needs to be done in the context of One Health.

GOVERNANCE

Background

Malawi has twenty-eight districts, which are further subdivided into areas governed by traditional authorities. These areas are further subdivided into villages, which are the smallest administrative units. For legislative purposes, each district is politically subdivided into constituencies that are represented by Members of Parliament in the National Assembly.

Eighty-five percent of Malawi’s population live in rural, hard to reach areas (>5 km or 3 miles from nearest health facility) (Local Governance Performance Index 2016). The Ministry of Health has placed Health Surveillance Assistants (HSAs) in all villages. Similarly, the Ministry of Agriculture has placed Assistant Veterinary Officers (AVOs) in all Extension Planning Areas (typically comprising 5-15 villages). There are environmental field officers in 16 of the 28 districts, currently.

National policies, plans, and strategies specific to One Health

Malawi lacks a unified policy and strategy for One Health; however, in collaboration with partners and stakeholders, several government ministries have developed strategic documents that address One Health related topics. Some of these documents describe how cross-disciplinary and cross-sector collaborations and engagement may be implemented.

The Public Health Institute of Malawi (PHIM), through MoH, is mandated to oversee implementation of One Health initiatives and activities in Malawi. However, no formal policy or legislation details this mandate, and no dedicated budget exists.

PHIM also promotes and implements a national health sciences research agenda which monitors, coordinates, and conducts research in national priority areas. The Malawi Department of Animal Health and Livestock Development (DAHLD) conducts livestock censuses and livestock disease surveillance, regulates livestock movement within country, issues permits for international livestock import/export, provides extension services for farmers including veterinary care, and coordinates multiple development initiatives. PHIM and the Department of Animal Health and Livestock Development (DAHLD) are currently jointly developing a One Health policy to facilitate surveillance and response to zoonotic disease and to address other common concerns. The proposed legislation will be publicly available once approved. At present, individuals from PHIM and DAHLD communicate regularly, largely on social media platforms, to keep one another informed of disease incidences/outbreaks, such as rabies, and have, in recent years, jointly responded to a few disease outbreaks.

National policies, plans, and strategies relevant to One Health

The Constitution of Malawi notes that the state has the responsibility “To manage the environment responsibly in order to (1) prevent the degradation of the environment; (2) provide a healthy living and working environment for the people of Malawi; (3) enable recognition to the rights of future generations by means of environmental protection; and (4) conserve and enhance biological diversity of Malawi.” Similarly, “the State shall actively promote the welfare and development of the people of Malawi by progressively adopting and implementing policies and legislation aimed at achieving adequate nutrition for all in order to promote good health and self-sufficiency.” Animals are not mentioned in the constitution.

The Public Health Act is being revised to embrace One Health. The current act was effected in 1948 and last amended in 1975. Sambala et al (2020) note “Consequently, existing policies and strategic plans that are meant to address gaps in public health and ensure coordinated effort lack support of laws and regulations.” and “Furthermore, although the Public Health Act outlines powers, duties and penalties, it fails to reinforce acceptable behaviour due to the insignificant penalties for noncompliance.”

The National Health Policy does not make any specific reference to One Health but does highlight “Inadequate communication mechanisms among Government, donors and implementing partners at each level.” Yet, the document outlines only limited roles for other ministries as regards human health. For example, “The Ministry responsible for Agriculture and Food Security will be responsible for development and implementation of policies and plans to ensure adequate and nutritious food supply.” And “Ministry responsible for Forestry, Mines and Environmental Affairs will be responsible for ensuring safety of employees and communities within and around the mines.” Relevant for future One Health initiatives, the document recommends “Empower[ing] communities to provide effective oversight of the community health system in line with decentralization policies of Government”

The Malawi Health Sector Strategic Plan II 2017-2022 aims to bring Malawi toward Universal Health Coverage (UHC) of quality, equitable, and affordable health care to improve health status, financial risk protection, and client satisfaction. Targets relevant to One Health include:-

- Target 3. By 2030, end the epidemics of AIDS, TB, malaria and Neglected Tropical Diseases, and combat hepatitis, water-borne diseases and other communicable diseases.

- Target 9. By 2030, substantially reduce the number of deaths and illness from hazardous chemicals and air, water and soil pollution and contamination

Priority goals relevant to One Health include:-

- Promote use of safe water and good sanitation practices

- Improve food safety and hygiene and nutrition services

- Promote safe working and living environments

- Strengthen vector and vermin control services at community and in public institutions

- Strengthen epidemic preparedness and response

- Encouragingly, the document notes “The health sector will also aim at strengthening inter-sectoral collaboration and partnerships.”

The Health Research Guidelines make no mention of intersectoral collaboration.

The National Community Health Strategy notes “planning and implementation gaps are common due to ongoing challenges with decentralisation; inadequate institutional coordination, especially between government and partners; fragmented data collection; and lack of sustained community engagement.” Interestingly, this document calls for standardization and harmonization of data collection methods and management within health sector, although no specific mention of harmonization with other sectors.

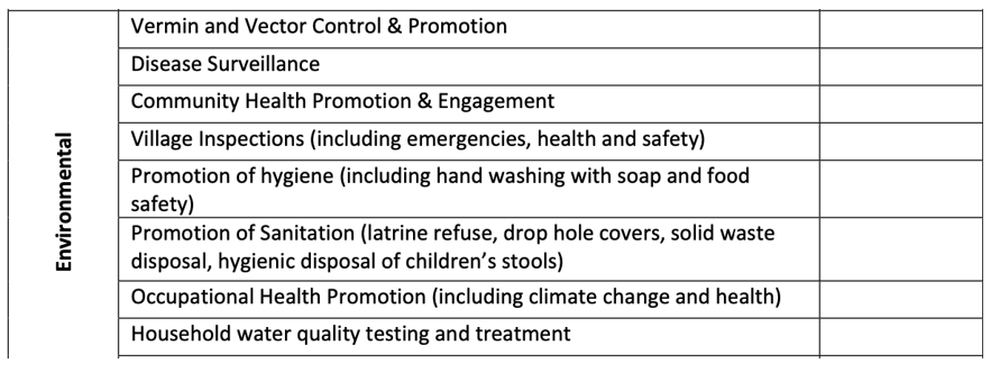

The document calls for community level interventions relating to environmental health:-

The Infection Prevention Guidelines makes no mention of zoonoses or the role of human-animal interactions or environmental conditions in infection prevention and control.

The Malawi National Health Information System Policy responds to international frameworks, most notably the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) in retrospect and the post-2015 Universal Health Coverage (UHC), which seeks to ensure, among other things, that all people receive quality health services that meet their needs without financial hardship in paying for them, as well as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). One Health is not mentioned specifically, although SDGs are relevant to One Health.

Using the cluster system, the Ministry of Disaster Management Affairs and Public Events and the Ministry of Health developed the COVID-19 Preparedness and Response Plan. The Plan outlines operational methods for COVID-19 readiness and response based on risks identified by the Ministry of Health (MoH) and WHO, as well as other emerging context-based factors.

The Malawi Antimicrobial Resistance Strategy aims to improve awareness and understanding of antimicrobial resistance through effective communication, education, and training; knowledge and evidence of AMR through research and surveillance; reduced incidence of infection through effective sanitation, hygiene, and prevention measures; ensure sustainable investment through research and development; and optimal use of antimicrobial medicines in human and animal health and agriculture.

The National Livestock Development Policy priorities relevant to One Health include:-

- Prevention and control of livestock diseases that threaten food security -- Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD), Contagious Bovine Pleuro- pneumonia (CBPP) and Rift Valley fever (RVF), Newcastle Disease, and African Swine Fever

- Enhancement of climate-smart livestock production

The document acknowledges effects of livestock production on the environment but does not make any recommendations. Veterinary public health is highlighted as a priority but no particulars are described. The livestock commercialization drive is in line with the Contract Farming Strategy. The policy does not integrate with policies on crop agriculture or wildlife.

The National Land Policy (2002) and Land Resources Management Policy and Strategy (2000) recognize competing land uses among livestock, crops, and other national investments. Few concrete recommendations are made.

The National Agricultural Policy informs the Agricultural Sector Wide Approach (ASWAp), which harmonises investments in agriculture and support programmes. Focus areas are:-

- food security and risk management,

- commercial agriculture, agro-processing, and market development; and

- sustainable agricultural land and water management. The ASWAp remains the main investment plan for agriculture in Malawi.

The Control and Diseases of Animal Act establish quarantine stations, limit animal imports and exports, and make Act-related rules. This Act also covers veterinary officer-ordered animal slaughter, animal inspections, stray animal seizure, and dangerous dog laws.

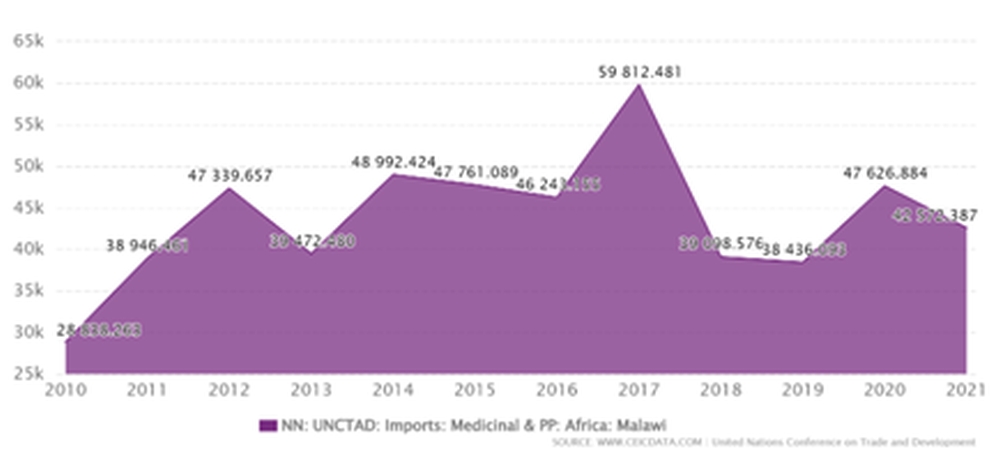

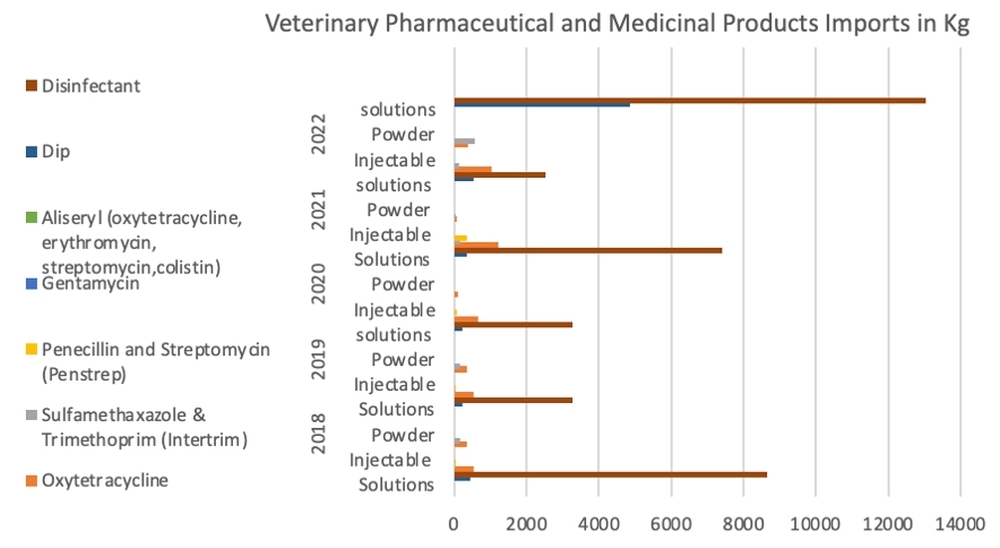

The importation of every medicinal or pharmaceutical products must meet requirements of Poisons and Medicine Regulatory Authority (PMRA). PMRA has a mandate to promote and improve health of the population of the country through regulation of pharmacy personnel, pharmacy business and medicine. Its mandate is to regulate medicine, allied substance, acaricides, disinfectants, feed additives, etc. locally manufactured or imported into the country. Other regulatory areas include issuing import permits, pharmovigilence and quality control. PMRA has a quality control laboratory to conduct analytical test on both human and veterinary medicines. PMRA does not have veterinary personnel, hence depends on Department of Animal Health and Livestock Development (DHALD) to issue import permits for veterinary products

The Prevention of Rabies Rules covers the prevention and control of rabies. It includes the notification, inspection, restrictions on animal movement, vaccination, dog marking, and destruction and disposal of diseased animals.

The 5-year National Fisheries and Aquaculture Policy (NFAP) addresses major challenges influencing fisheries and aquaculture development in Malawi, such as the need to increase monitoring and evaluation and use Public-Private Partnerships (PPP). The Policy aims to sustainably boost fisheries and aquaculture productivity for nutritious food and economic growth.

The Biosafety Act covers the biotechnological activity safety and related matters. The Act regulates genetic modification and related activities to protect public health and the environment. The Act covers genetic modification, importation, development, production, testing, release, use, and application of genetically modified organisms, and gene therapy in animals, including humans.

The Malawi National Resilience Strategy is a cross-sectoral document that has four pillars.

- Resilient Agricultural Growth, including smallholder farming interventions; access to inputs, training, and asset creation; diversification in the production and marketing of crops, forestry, livestock, and fisheries; and reduction in maize dependence;

- Risk Reduction, Flood Control, and Early Warning and Response Systems;

- Human Capacity, Livelihoods, and Social Protection

- Catchment Protection and Management to develop and adopt integrated watershed management.

The National Climate Change Management Policy, (2016) was formulated by the Ministry of Natural Resources, Energy, and Mining Environmental Affairs Department. The policy states that natural resources are Malawi's main source of social and economic development and lists the following critical issues:-

- climate variability

- inadequate institutional capacity for addressing climate change

- inadequate mainstreaming of climate change problems

- inadequate enforcement of climate-relevant legislation

- increasing deforestation and unsustainable land use

The Malawi Growth and Development Strategy (MGDS) III - Building a Productive, Competitive and Resilient Nation aims to make Malawi productive, competitive, and resilient through sustainable economic growth, energy, industrial, and infrastructure development while tackling water, climate change, environmental management, and population issues.

The Environment Management Act, 2017 makes provision for the protection and management of the environment; the conservation and sustainable utilization of natural resources and for matters connected therewith and incidental thereto. It notes “(1) Every person has the right to a clean and healthy environment and has the duty to safeguard and enhance the environment.” It provides little specific initiatives on how an individual can safeguard or enhance the environment.

The National Environmental Health Policy focuses on service gaps that disproportionately affect the health of the poor and the disadvantaged populations, with priority problems being communicable diseases, malnutrition, and injury.

The Water Resources Act, 2013 provides for the management, conservation, use and control of water resources; for the acquisition and regulation of rights to use water.

The National Irrigation Policy calls for enhanced land and water productivity through sustainable land tenure arrangements, catchment management, and water harvesting. The document requests cooperation from the Ministry of Agriculture and the Department of National Parks and Wildlife.

The Malawi National Charcoal Strategy calls for investments in alternate energy including alternate cooking methods and livelihoods.

Soil Conservation Policy Brief encourages practices to reduce water loss from runoff and evaporation and to increase soil fertility using crop rotation, fallowing, intercropping, applying animal / green manure, composting (ideally as part of an integrated crop-tree-livestock system), and by applying supplementary inorganic fertilizer as needed.

The Plant Protection Act details the roles of plan inspectors but does not have set targets.

The National Parks and Wildlife (Amendment) Act and associated Regulations clearly outlines strategy and methodology to combat wildlife crime and improve protection of National Parks’ lands.

The National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan II 2015-2025 has 16 targets related to conservation of biodiversity with few specific strategies.

The National Disaster Risk Management Policy does not describe a clear platform for ministry collaborations and does not have a clear financial plan.

The National Seed Policy calls for further legislation to regulate of seed management in Malawi. There is little to no mention of livestock, wild habitats, or human health.

The National Food Safety Act is aimed at protecting the consumer against unsafe, impure and fraudulently presented food that may be injurious to the health of the consumer and also ensure fair food trade.

The National Forest Policy takes a holistic approach to sustainable forest management. It adequately addresses issues of forests and water; climate change; food security; HIV and AIDS; gender and equity; wealth creation; biodiversity and Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES); Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) and Clean Development Mechanisms (CDM). The policy aims to create and protect “landscapes that provide clean water and air reduce the prevalence of disease.”

Malawi outlines its climate change and health priorities in the National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA). The document highlights the urgency planning for potential risks caused by recurrent floods and droughts as well as their effects on human well-being and ecologies are highlighted in the country’s adaptation plans. Secondly, the document urges addressing the spread of climate-sensitive diseases such as food borne illness and malaria, while responding to declining access to food / agricultural production, which may result in increased levels of undernutrition, is a priority. Finally, the NDC highlights efforts aimed at enhancing local institutional and human resource capacity in order to provide sustainable disease monitoring, prevention and control.

Malawi 2063 is a long-term, multi-sectoral national strategy for Malawi for the years 2020-2063. Its primary purpose is to convert Malawi into a youth-centered, inclusive, prosperous, and self-reliant upper middle-income industrialized nation. To this end, it outlines measures aimed at establishing a strong economy with a competitive manufacturing industry, driven by productive agriculture and mining sectors; world-class urban centers and tourism hubs with requisite socio-economic amenities for a high quality of life; a united, peaceful, patriotic nation, with people actively participating in building their nation; an effective governance system and institutions that strictly adhere to the rule of law; and a high-performing education system; a high-performing and professional public sector as well as a dynamic and thriving business sector; globally competitive economic infrastructures and human resources; an economically sustainable environment.

The intersectoral National Gender Policy 2015 seeks to incorporate gender in the national development process to increase women's, men's, and girls' engagement in sustainable and equitable poverty-eradication. The first National Gender Policy of 2000 emphasized the lack of attention paid to rising concerns including HIV and AIDS, gender-based violence (GBV), human trafficking, increased environmental degradation, climate change, and elevated levels of poverty in the country, all of which have a gender dimension. The Gender Policy encourages women, men, girls, boys, and other vulnerable groups to participate in natural resources, environment, and climate change initiatives to make livelihoods more disaster resistant.

The National Education Policy (NEP) – 2013 and National Education Sector Investment Plan (NESIP) 2020-2030 do not reference One Health.

The above publications, policy documents, mandates from government entities that pertain to One Health are available at:-

- https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1QZSqmK6phv-idfsGBdCsMkocdissVanh?usp=share_link

Actors in One Health Governance

Multiple ministries within Malawi Government are actors in One Health. Malawi also has a wide network of committed international and local partners to improve its One Health activities.

- Ministry of Health

- Ministry of Finance

- Ministry of Labour

- Ministry of Education

- Ministry of Gender, Community Development and Social Welfare

- Ministry of Local Government

- Ministry of Justice

- Ministry of Agriculture

- Ministry of Natural Resources and Climate Change

- Ministry of Energy

- Ministry of Water and Sanitation

- Ministry of Trade and Industry

- Ministry of Transport and Public Works

Non-Governmental Organizations, Civil Society Organizations, Faith-Based Organizations, and Traditional Leaders advocate for increased resources for the health sector; they serve as a bridge between the government and the community to enable the community to have access to services. These include:-

- Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation

- University of North Carolina

- Baylor College

- Johns Hopkins University

- University of Maryland

- Médecins sans Frontières

- Malaria Alert Center

- Lighthouse

- London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

- Liverpool University (Wellcome Trust)

- DREAM Project (Italian DIGNITAS International)

- Save the Children

- Action Aid

- TB Care

- Fleming Fund

- Malawi Epidemiology and Intervention Research Unit (MEIRU)

- University of Maryland Baltimore

- International Training and Education Center for Health (I-TECH)

- GIZ

- Project Hope

- Plan international

- Partners in Health

- African Institute for Development Policy (AFIDEP)

Parallel organizations in the animal health sector include:-

- Lilongwe Society for the Protection and Care of Animals

- Blantyre Society for the Protection and Care of Animals

- Mission Rabies

- Lilongwe Wildlife Trust

- African Parks

- Peace Parks

- Carnivore Research Malawi, Bat Research Malawi

- Heifer International

- International Fund for Animal Welfare

- Interaide

- Small Scale Livestock and Livelihood Program

Parallel organizations in the environmental sector include:-

Action for Environmental Sustainability Malawi

- Centre for Environmental Policy and Advocacy

- Wildlife and Environmental Society of Malawi

- Mulanje Mountain Trust

- Malawi Green Action

- Habitat for Humanity

- Plan international

- World University Service of Canada

Funding Mechanisms

The Sector Wide Approach (SWAp) is the GOM funding mechanism for the health sector and, similarly, the Agricultural Sector Wide Approach (ASWAp) is the GOM funding mechanism for the agricultural sector. Both include basket pool funding and discrete funding. The planning mechanisms are a collaborative effort between all pool and discrete funding partners. USG partners (US Embassy, USAID, CDC, PEPFAR), European partners (Norwegian, German, GAVI (Nordic countries), Japan (JICA etc.), FCDO (United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland), other parastatals (WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Meteorological Organization, WOAH, World Bank, African Union) are among the partners that provide technical and financial support.

There are movements towards creating a funding basket for climate change activities in Malawi (CEPA report). Funding of other environmental activities remains piecemeal.

Currently, there is little sharing of funding between sectors.

Overall Strengths in One Health Governance

- A supportive legislative framework exists with identified areas for improvement and collaboration

- Malawi's ministries endorsed the concept note and roadmap for One Health

- The Public Health Act, DODMA Act, and draft PHIM Bill are under review and will align with efforts to strengthen One Health capacities.

- Multidisciplinary capacity (epidemiologists, veterinarians, clinicians and laboratory specialists, environmental engineers) is available at the national level and in some provinces.

- A National Disaster Appeal Fund for emergency use sits within DODMA and is available for certain public health emergencies and natural disasters.

Gaps in One Health Governance

- One Health is not a high political priority, and there is no One Health policy or strategy in place to advance the One Health platform. The One Health platform collaboration between PHIM and DAHLD remains in draft form.

- Responsibility for One Health concerns have been designated to PHIM under the Ministry of Health. However, there is no formal mandate to conduct One Health work or budget to do so. A multidisciplinary One Health task force is only occasionally active on an ad hoc basis.

- PHIM and EAD have no legal mandate.

- Many existing policies that contribute to One Health topics are out of date.

- Formal agreements and MOUs outlining roles, responsibilities, information sharing practices and collaboration between ministries and enforcement entities are lacking. Responsibilities for implementation of policies relevant to One Health are not clearly assigned.

- Funding to enact and maintain policies pertaining to One Health at almost all government ministries is insufficient and insecure. Most policy development and implantation are donors funded. Budget planning and development for joint ventures among different ministries and departments is poorly coordinated.

- Contingency funding for emergency response is not accessible rapidly (for example within 24 hours).

- Communication and coordination are informal (via WhatsApp, for example), and based on professional connections rather than policies or procedures.

- Most intersectorial communication/collaboration and stakeholder engagements are event-driven rather than regularly scheduled.

Zoonotic Disease Policies

- There is a list of five zoonotic diseases of the greatest public health concern generated by the animal health sector (rabies, bovine tuberculosis, brucellosis, cysticercosis, and human African trypanosomiasis). The prioritization of these diseases is based on their transmission potential and incidence, outbreak potential, socio-economic implication, severity of disease or case fatality rate, and international public health implications

- Malawi employs the IDSR guidelines as surveillance framework (Joint External Evaluation of IHR Core Capacities of The Republic of Malawi Report 2019)

- A clear structure for reporting zoonotic diseases exists that includes the assignment of animal health officers in communities and area supervisors overseeing a wider geographic area. In reality, reporting/surveillance is patchy at best due to lack of human resources, poor infrastructure, and inadequate data management systems.

- No system of exchange of epidemiological information on zoonotic diseases between DAHLD and PHIM, except informally via the WhatsApp smartphone messaging app. No regular surveillance bulletins exist for zoonotic diseases

- MOUs are in place for rabies surveillance and monitoring with two non-governmental organizations (NGOs); the Lilongwe Society for Prevention and Cruelty to Animals and Mission Rabies.

- Frameworks of agreement for cross-border collaboration on animal transport with Zambia and Mozambique are established, but the operationalization of the framework of agreement with Zambia and Mozambique is suboptimal having no quarantine services or standardized security procedures. There is no established framework with the United Republic of Tanzania.

AMR Policies

- Malawi is a signatory to the United Nations Political Declaration on AMR and the World Health Assembly Resolution (WHA 68.7) that urges member states to have in place National Action Plans (NAPs). Malawi is thus amongst the UN member states that endorsed the Global Action Plan (GAP) which was developed by a tripartite collaboration of the WHO, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO)and the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH) which integrated the One Health Approach as a blueprint for developing its NAP.

- Malawi has a multisectoral AMR strategy and plan (2017-2022) that is costed, approved and launched.

- The multisectoral coordination structure for AMR (Technical Working Group) under the MoH is functional.

- A national microbiology reference laboratory for AMR detection and reporting, and a national AMR surveillance system with nine priority pathogens, are incorporated into the IDSR.

- There is a national antibiotics selection committee for human health but not for veterinary purposes.

- There are national treatment guidelines and an essential drugs list for human health but not for veterinary purposes.

- There is inadequate dissemination of the AMR strategy and plan at all levels to ensure stakeholders are aware of its content and of their roles and responsibilities.

- A system to monitor and evaluate implementation of the AMR strategy is not in place.

- The national AMR strategy captures activities that ensure the appropriate use of antibiotics in humans but not in animals.

Foodborne Illness Policies

- Several foodborne pathogens are identified as priority diseases under IDSR; surveillance indicators and guidelines include case definitions, actions to respond to suspicion, data analysis, sampling and laboratory testing.

- Food laws and regulations are poorly coordinated, outdated or incomplete and do not extend to informal markets and mobile vendors. (Lazaro et al 2019)

- A national IPC programme for human health, animal health and food production is needed which includes finalized draft IPC policy and guidelines

- Overall, regulatory framework is uncoordinated, outdated or incomplete with poorly defined mandates and dissemination strategy. (Morse et al 2018)

- Some coordination structures exist, such as the health committees and WASH clusters.

Landscape Health Policies

- Multiple institutions and statutory agencies deal with land, resulting in confusion over jurisdiction and inadequate policy intervention

- Sharing mechanisms of ecological benefits and natural resources between forest and lake dependent communities, district and central government authorities are unclear

Feeds, Forages, and Plant Health Policies

- Such policies are overall limited in scope with no reference to related sectors such as nutrition, livestock, water management, etc

Climate Change Policies

- The national climate change policy “provides strategic direction for Malawi's priorities for climate change interventions and outlines an institutional framework for the application and implementation of adaptation, mitigation, technology transfer and capacity building measures.” (CEPA 2010)

- The Climate Project Steering Committee holds regular meetings with published minutes

EDUCATION

In Malawi, explicit One Health education is generally limited. While the One Health concept is implicitly covered in some undergraduate and postgraduate courses, particularly those related to human health, veterinary and animal health, and environmental health sciences, what is provided is insufficient. Despite this background, recognition of this concept and its importance among researchers and scholars in the country appears to be growing. Despite this, much work remains to be done in terms of curriculum development, capacity building, research and knowledge dissemination, institutional framework, and infrastructure development for one health research and education, and policy.

One Health education in primary schools

- Mission Rabies has education over 1 million primary school children in the southern region about the risks of rabies and actions to take if a person is bitten by a dog.

- Lilongwe Wildlife Trust has educated hundreds of thousands of primary school children in the central region on environmental stewardship and biodiversity.

- No formal One Health education exists

One Health education in secondary schools

- None

One Health education in universities

Malawi University of Science and Technology (MUST)

i. Undergraduate level

One health education is covered implicitly. Bachelor’s courses of note include:-

- BSc in Immunology

- BSc in Medical Microbiology

- BA in Indigenous Knowledge Systems and Practice

- BSc in Geo-Information and Earth Observation Science

- BSc in Water Quality Management

- BSc in Sustainable Energy Systems

- BSC in Disaster Risk Management

- BSc in Science in Meteorology and Climate Science

- BSc in Earth Science

ii. Postgraduate level

- MUST has officially launched postgraduate programs in One Health: the Master of Science in One Health and the Doctor of Philosophy in One Health. The Ndata School of Climate and Earth Sciences oversees these two programs. The first cohorts for both programs are expected to begin their studies in the academic year 2022/23.

- The MSc in One Health is a two-year program spread across four semesters. Students must complete course work in the first year and a One Health-related project in the second year to complete this program. The curriculum for this program aims to develop capacity and expertise in addressing emerging ecosystems, animal, and human health issues to reduce economic and human losses caused by natural and anthropogenic crises. The goal is to train and educate well-equipped workforces to deal with interconnected and interrelated health challenges at the human-animal-environment nexus.

- The PhD in One Health is a three-year program that includes six months of course work and two and a half years of intensive research. The research focuses on the increasing interactions between humans and animals in the environment, as well as numerous factors exacerbating ecological health and, the emergence, re-emergence, and spread of infectious diseases, as well as other growing threats to human and socioeconomic wellbeing, all of which necessitate multisectoral and multidisciplinary collaboration and coordination on prevention through environmental management.

Kamuzu University of Health Sciences (KUHeS)

i. Undergraduate

- KUHeS offers multiple bachelor’s degree in medicine and nursing. One health is implicitly covered in the course work required for these degrees. For example, Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) and Disease Transmission Dynamics (DDT) are core courses for most degrees offered. The importance of animals and animal health in the management of some epidemic-prone diseases is emphasized in this course. The DDT course investigates the roles of the environment and animals in disease transmission.

ii. Postgraduate

- KUHeS offers a Master of Health Sciences in antimicrobial stewardship at the postgraduate level. This master's program is health-related, and it educates students on antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and the importance of animal health on AMR, given that animals use a lot of antibiotics. The following master's programs include One Health-related components:

- Master of Public Health

- Master of Epidemiology

- Master of Global Health Implementation

Lilongwe University of Agriculture and Natural Resources (LUANAR)

One health is not offered as a full program or as a course at the undergraduate or postgraduate levels. However, the concept is covered implicitly in course work of many degrees such as public health and infectious diseases courses within the veterinary medicine and animal science curriculae. Other courses of note:-

i. undergraduate

- Bachelor of Science in Agribusiness Management

- Bachelor of Science in Agriculture Economics

- Bachelor of Science in Agricultural Development Communication

- Bachelor of Science in Agricultural Education

- Bachelor of Science in Agricultural Enterprise Development and Microfinance

- Bachelor of Science in Agricultural Extension

- Bachelor of Science in Development Economics

- Diploma in Youth and Development

- Diploma in Gender and Development

- Bachelor of Science in Gender and Development

- Bachelor of Science in Food Science and Technology

- Bachelor of Science in Human Nutrition and Food Science

- Bachelor of Science in Human Sciences and Community Services

- Bachelor of Science in Agroforestry

- Bachelor of Science in Aquaculture and Fisheries Science

- Bachelor of Science in Forestry

- Bachelor of Science in Environmental Science

- Bachelor of Science in Natural Resources Management (Land and Water)

- Bachelor of Science in Natural Resources Management (Wildlife and Ecotourism)

ii. post-graduate

- MSc in Gender and Development

- MSc in Human Nutrition

- MSc in Food Science and Technology

- MSc in Agribusiness Management

- MSc Science in Agriculture Education

- Master of Science in Extension

- MSc in Agroforestry

- MSc in Aquaculture

- MSC in Environment and Climate Change

- MSc in Social Forestry

- PhD in Aquaculture & Fisheries

- PhD in Agricultural & Resource Economics

- PhD in Agriculture & Applied Economics

- PhD in Animal Science

- PhD in Aquaculture & Fisheries

- PhD in Biotechnology

- PhD in Rural Development (Agricultural Economics or Agricultural Extension Option)

LUANAR also hosted a One Health summer school in September 2022 to promote one health education throughout the country. 'ONEHEALTH4DEVELOPMENT' 2022/23 targeted young scientists (PhD students and early career postdocs 4 years after PhD) from Africa and Germany. This two-week training was hosted by LUANAR and coordinated by Universitat Tubingen, LUANAR, Universitat Hohenheim, and Kamuzu University of Health Sciences. It took place between September 19th and September 30th, 2022. LUANAR will also host a similar training in 2023. The same collaboration generated a policy document “Innov8Health” which advocates that partner institutions should “promote and support sustainable transformation and development in Africa by joining forces, strengthening research capacities, and intensifying cooperation across disciplines and sectors to achieve these goals.” Many potential One Health research collaborations are suggested (Changulnda et al 2021).

LUANAR, in conjunction with University of Edinburgh, is co-hosting an advanced epidemiology training targeting professionals and researchers in human, animal, and environmental sectors in 2022 and 2023. This initiative is funded by the Global Challenges Research Fund.

Mzuzu University

Mzuzu University, similarly, does not offer explicit One Health degrees or courses but covers One Health concepts within several degrees.

i. undergraduate

- Bachelor of Education (Sciences)

- Bachelor of Science (Forestry)

- Bachelor of Science (Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences)

- Bachelor of Science (Renewable Energy Technologies)

- Bachelor of Science Land Management

- Bachelor of Science (Water Resources Management and Development)

- Bachelor of Science (Value Chain Agriculture)

- Bachelor of Science (Transformative Community Development)

- Bachelor of Science (Biodiversity and Conservation Management)

- Bachelor of Science (Parasitology and Disease Vector Control)

- Bachelor of Science (Nursing and Midwifery)

- Bachelor of Science (Biomedical Sciences)

ii. postgraduate

- Master of Science (Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences)

- Master of Science (Forestry)

- Master of Science (Sanitation)

- Master of Science (Water Resources Management and Development)

- Master of Science (Urban and Regional Planning)

- Master of Science (Geographical Information Systems)

- Doctor of Philosophy (Water and Sanitation)

- Doctor of Philosophy (Geographical Information Systems)

- Doctor of Philosophy (Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences)

Some postgraduate students (MSc and PhD levels) are working on One Health-related research project at Malawi Liverpool Wellcome Trust (MLW), particularly in the subject areas of zoonotic disease and AMR. Short courses with components of One Health are also occasionally offered at MLW with topics such as zoonotic disease, antimicrobial stewardship, and epidemiology and statistics.

Field Epidemiology Training Program (FETP)

The Ministry of Health (MoH) with support from United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) established the Field Epidemiology Training Program - Frontline in Malawi in 2016. The FETP-Frontline was designed to be a continuous training program within PHIM with the goal of training public health staff in surveillance. The Malawi FETP-Frontline course has graduated forty-seven trainees since its inception. Six national mentors have also been recruited for the program. The Malawi FETP-Frontline program has held frontline courses in five districts spread across the country's three regions (Northern, Central, and Southern). To embrace the One Health approach, each cohort has included at least one trainee from the Department of Animal Health.

NORAD One Health Education and Research Project

The Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD) funded the One Health Education and Research project (https://en.uit.no/project/onehealth). The project brings together a multidisciplinary consortium from The Arctic University of Norway (UiT), the Norwegian Veterinary Institute (NVI), the Norwegian Institute of Bioeconomy Research (NIBIO), Addis Ababa University (AAU), and the Malawi University of Science and Technology (MUST) to address gaps in One Health professional training at AAU (Ethiopia) and MUST (Malawi).

This project has five pillars that apply to Malawi, which are as follows:

- Development of a single health curriculum at MUST

- Capacity building for MUST staff and students

- Implementation of One Health research in Blantyre

- Engagement and knowledge dissemination with relevant stakeholders

- Improving One Health education and research systems, infrastructure, and equipment.

Strengths in One Health Education

- Establishment of One Health MSc and PhD at MUST

- Many undergraduate and undergraduate programs relevant to One Health

- Select short courses on One Health delivered with positive reception

Gaps in One Health education

- There are no deliberate policies to promote One Health education.

- Limited cohesion among human, animal, and environmental health scholars and researchers

- No or limited inclusion of designated one health education course in the primary, secondary, and tertiary curriculums (with an exception of newly advertised programs at MUST)

- Currently, most public and private academic institutions do not provide formal One Health training. .

- Academic health education institutions do not have deliberate strategies to ensure collaboration among animal health, human health, and environmental health sciences.

- Limited incentives to retain existing public health, veterinary, and environmental science workforce in country

Despite the 50% increase in the health workforce that was achieved through the implementation of the 6-year Emergency Human Resources Plan (2005-2010), the challenge still remains to sustain the gains. The government has in recent years not been able to absorb all the health and veterinary workers coming out of the training institutions due to inadequate financing, infrastructure and equipment (Jerving 2018, personal experience Wood)

Publications, policy documents, mandates and course descriptions related to One Health education are available at

- https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1yRry2EObKpOL-2uuettmxr4LFcu-0hSe?usp=sharing

and further detailed in Appendix 2

- https://docs.google.com/document/d/1jNKRe-NizI4uWJZJn_B9mXBUmgAWSaQI/edit?usp=sharing&ouid=117223745126922437139&rtpof=true&sd=true

IMPLEMENTATION OF ONE HEALTH ACTIVITIES IN MALAWI

Zoonotic Disease

- Multisectoral response teams conduct active surveillance during outbreaks when resources are available

- Strategies to conduct point-of-care and farm-based diagnostics exist but do not cover all priority diseases and are not accessible to most of the country

- The WOAH delegate has filed reports on zoonotic outbreaks occurring in Malawi in 2018, in accordance with WOAH processes but not since.

- WhatsApp smartphone messaging groups have been set up for informal, rapid information sharing, both in Malawi between PHIM and DAHLD staff, between the NFP and WOAH delegate, and between neighbouring country NFPs (Zambia, Mozambique and the United Republic of Tanzania).

- Several electronic tools are being piloted to assist with immediate notification, weekly reporting and syndromic surveillance.

In past years, there was growing concern that many human cases of rabies encephalitis in Malawi were undiagnosed or misdiagnosed (Depani et al 2012). Clinicians working at the Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital in Blantyre, Malawi, reported a threefold increase in the number of paediatric rabies cases in 2012 compared to the period 2002–2005. This concern led to the formation of a public private partnership in 2015 between the UK-based charity Mission Rabies and the Malawi Department of Animal Health and Livestock Development (DAHLD).

Since that time, this partnership has vaccinated hundreds of thousands of dogs in 3 districts in southern Malawi — Blantyre, Chiradzulu, and Zomba -- in both urban and rural areas. The vaccination campaigns have consistently achieved over 70% vaccination coverage, and, since 2015, the number of paediatric rabies cases presenting to the Central Hospital has declined significantly, thus proving the feasibility of rabies control in diverse, low-resource settings.

We did not come across ongoing initiatives for other zoonotic disease mitigation.

AMR initiatives

- Some 40% of laboratories have the capacity to detect, isolate and identify antimicrobial-resistant organisms in humans, and 20% of hospital laboratories are enrolled in WHO GLASS.

- For antimicrobial sensitivity testing, the National Microbiology Reference Laboratory employs the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing standards.

- The Universities of Tromso and Kwazulu Natal provide technical assistance in the AMR surveillance system. (WHO 2022)

Foodborne illness initiatives

- Most health facilities have some IPC SOPs and implementation of IPC/WASH activities. (WHO 2019)

Landscape health management, interface of wildlife/protected areas initiatives

- The Community Based Rural Land Development Project funded by World Bank provides grants for community acquisition and distribution of land in support of rural poor

- The Agricultural Commercialization Project funded by World Bank supports subsistence farmers to expand to commercial operations.

- Shire Valley Transformation Program funded by World Bank aims to increase agricultural productivity through irrigation.

- African Parks conserves and rehabilitates large National Parks (Liwonde and Majete) and runs strong community outreach projects around the parks.

- The Protected Areas Management Group advocates for protection of Lake Malawi National Park

- The Fisheries Management Group aims to establish a “Participatory Resource Monitoring Method” and encourages value addition to fish.

- Multiple NGOs have small scale tree-planting projects and permaculture projects.

- The Improved Forest Management for Sustainable Livelihood Programme (IFMSLP) has developed management plans for village forestry areas in 12 districts in Malawi focusing on:-

- Training of local communities in alternative livelihood activities

- Delivery of community livelihood analysis and forest resource assessment

- Increased smallholder agricultural productivity gives scope for CSA practices to be adopted, including agroforestry

- The Malawi Youth Forest Restoration Programme (MYFRP) provides youngpeople with training and jobs, protect the environment, and foster environmental stewardship throughout the country to help implement the National Forest Landscape Restoration Strategy

Feeds, forages, plant health initiatives

- The GoM Affordable Inputs Program allows Malawian subsistence farmers to purchase farm inputs at a subsidized cost with the government paying over 70% of the cost. The program allows for purchase of open pollinated and hybrid maize seed, sorghum seed, rice seed, bean seed, ground nuts seed, soya beans seed, pigeon and cowpea seed, and fertilizer . The programme has been very popular and successful; however, international price inflation on materials such as fertilisers threatens the sustainability of the programme. (Mangazi 2022)

- ASWAp is encouraging multi-cropping and integration of livestock and crop agriculture and integrated soil fertility management practices such as use of organic manure, residue management, use of nitrogen fixing tree crops.

- CRISAT-ILRI Crop Livestock Integration and Marketing in Malawi (CLIM²) seeks to “improve crop-livestock diversification and contribute to the more efficient use of scarce farm resources.”

Climate Change initiatives

- Farmers have adopted on-farm work, drought-tolerant varieties, early planting, and intercropping to reduce extreme climate impacts. Farmers adopted drought- and disease-tolerant crops, diversified their crops, planted earlier, did more on-farm work, and changed their eating habits. Social networks and capital influence farmers' adaptation decisions (Abid et al 2020)

- The Tree Planting and Management for Carbon Sequestration and other Ecosystems Programme was launched in January 2007.

- Multiple clean-cooking initiatives exist, some using agricultural waste rather than charcoal such as ZipoStoves.

Initiative Gaps

Zoonotic Disease gaps

- Surveillance systems for most diseases are weak or non-existant

- There are inadequate ante- and post-mortem inspections at abattoirs and associated premises.

- There is a shortage of veterinarians in public health.

- The veterinary service has diagnostic challenges in laboratory diagnosis of zoonotic diseases. Required equipment and reagents are not available for some testing procedures.

- Collaboration between the human and animal sectors diagnostics needs strengthening and formalizing.

- Regular bulletins (including analysis of epidemic-prone disease thresholds) are not produced and disseminated to all stakeholders for animal or human health.

AMR gaps

- AMR surveillance data does not include data from animal sources.

- There are no guidelines for antibiotic use in animals.

- There are no sentinel sites for surveillance of infections caused by AMR pathogens in livestock.

Foodborne illness gaps

- No formal surveillance on food safety exists.

- Detection of foodborne pathogens between the human and animal health sectors is poorly coordinated.

- Resources for effective food inspection and enforcement are inadequate

- These is limited awareness ability to comply with limited awareness and ability to comply with existing standards in informal markets. (Morse 2018)

Landscape health gaps

- There is inadequate alternate energy supply to slow deforestation for fuel for cooking.

- Most farmers grow a single crop, maize, with inorganic fertilizer exclusive of micronutrients.

- Most farmers are unaware of how to restore soil health

The effects of climate change, particularly changing rainfall patterns, on natural habitats is not well monitored.

Feeds, forages, plant health gaps

- Most farmers do not integrate crop and livestock agriculture.

- Most farmers do not have access to adequate pasture so, if raising larger livestock, gather forage by hand.

- Most farmers are unaware of alternate feeds such as silage.

Climate change gaps

- Overall, Malawi’s vulneratbility to climate change is linked with poverty and macroeconomic instability.

REFLECTION ON THE DESKTOP REVIEW

Despite the large number of published resources, the desk review identified information gaps. The information on foodborne illnesses was very limited and scattered. There are some excellent opportunities to obtain the stewardship of international partner bodies dealing with One Health, and these should be taken advantage of. More communication among GOM and NGO actors would be beneficial, and communication should be formalized and standardized around pre-determined topics.

MONITORING AND EVALUATION

Incidence of focal OH disease

The Malawi Ministry of Health's Central Monitoring and Evaluation Division (CMED) developed the Monitoring and Evaluation Health Information Systems Strategy (MEHIS) 2018-2022 to guide the Ministry's implementation of priority interventions to strengthen Malawi's health inform

ation system and ensure that it can generate and use high-quality data to monitor and evaluate its Health programs.

Malawi's health data and information systems are managed by CMED. DHIS2 has been adopted by the MoH and rolled out to all districts.

These issues persist:

- vertical/parallel reporting structures

- lack of HIS subsystem interoperability

- poor data quality

- over-reliance on (and too many) manual data collection tools

- insufficient capacity and alignment of research activities

- insufficient human resources for MEHIS

- insufficient coordination in MEHIS activity implementation.

Thus, while the human health sector has multiple systems of disease surveillance, they do not act in concert and data is not readily available, and, indeed non-existent for specific diseases. Medical records at the two major hospitals, Queen Elizabeth in Blantyre and Kamuzu Central in Lilongwe, are paper and inconsistent.

Currently, DAHLD is expanding the FAO-developed smartphone-based EMA-i programme for zoonotic disease surveillance from 6 to 9 districts. However, the system has many technological issues limiting the consistent collection of surveillance data and also limiting the availability of information to stakeholders. Currently only 2 months of data are available from select districts. (FHO 2015)

Multiple recent investigations into available zoonotic disease data available at the DAHLD have shown that some but not all Agricultural Development District Offices (ADDs) have sporadic paper records but that no central database exists.

A past review of CVL diagnostic records cannot be assumed to be consistent with actual disease prevalence due to significant testing and laboratory access bias (Wood et al 2021). Original data is in Appendix 3.

- https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/16ILq-pUBFyfvgkuG9W9jl7tTbX4UC6pz/edit?usp=sharing&ouid=117223745126922437139&rtpof=true&sd=true

The UK-based NGO Mission Rabies has used a bespoke smartphone application to monitor animal and human rabies cases in Blantyre district since 2015; this data is cloud-based and publicly accessible.

Zoonotic diseases – human data

Rabies – human data

All paediatric rabies cases that presented to Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital in Blantyre, Malawi, between May 2012 and May 2017 were identified and analysed as part of a mass canine rabies vaccination program evaluation. The fourteen paediatric rabies cases (10 males and four females) ranged in age from three to eleven years. (Gibson 2016)

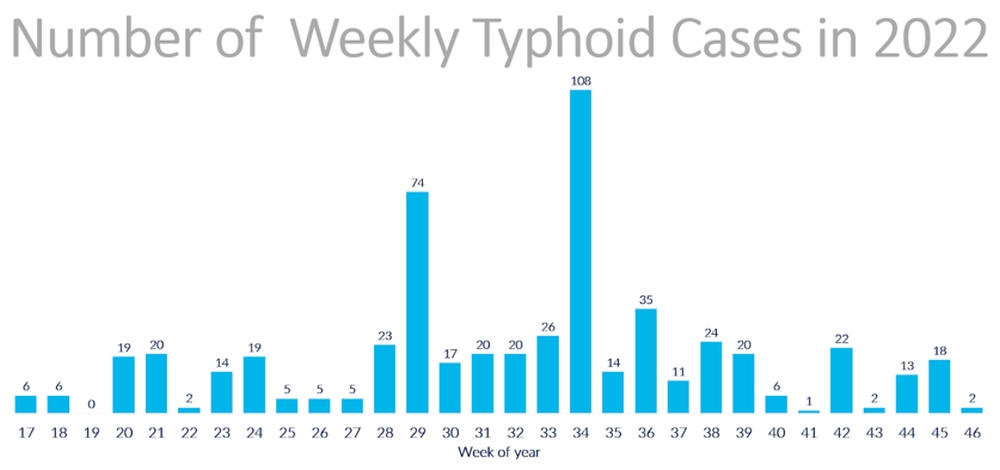

According to PHIM/IDSR data, the number of weekly rabies cases nationwide in 2022 proved to be sporadic and irregular.

Bovine tuberculosis – no data in humans

Brucellosis – no data in humans

Cysticercosis – human data

- A team from London School of Tropical Diseases and Malawi Liverpool Welcome Trust is seeking ethical approval to review medical records at the two larger hospitals in country; however, personal communication with a pathologist at Queens Hospital suggests that this data will not be of sufficient quantity or reliability to draw conclusions.

Human African trypanosomiasis – human data

- Between 2009 and 2018, there were 263 new cases of T. b. rhodesiense HAT reported. In particular, 27 cases were reported 2017 and 24 in 2018. In Rumphi and Mzimba Districts, 5.9 and 1.9 human trypanosome infections per 100,000 people were reported in 2015, respectively. Kasungu, Ntchisi, and Nkhotakota Districts reported 0.6, 0.4, and 0.3 cases per 100,000 people respectively (Chimera 2021).

Zoonotic Disease – animal data

Rabies – animal data

- Records of positive rabies cases at the Central Veterinary Laboratory are available; however, as previously noted, this data base cannot be considered to be representative.

Bovine tuberculosis – animal data

- No formal government data available other than from CVL records.

- Select abbatoirs have records on positive bTB cases.

- Southern and central cattle were more likely than northern cattle to have bTB-like lesions at slaughter with up to 42% prevalence. Females, older cattle, and crossbreds were more likely than males, younger animals, and Malawi Zebu breeds to develop bTB-like lesions. (Kapalamula 2022).

Brucellosis - animal data

- No formal government data

- A cross-sectional study was conducted in the southern region from January 6 to February 27, 2020, to estimate the seroprevalence of brucellosis in dairy cattle herds among smallholder farmers, government, and private dairy farms. The study was unable to detect brucellosis; however, current ongoing studies have detected positive cases (Kothowa et al 2021)

Cysticercosis-animal data

- No formal government data other than from CVL records.

- Select abbatoirs have records on positive T.solium cases.

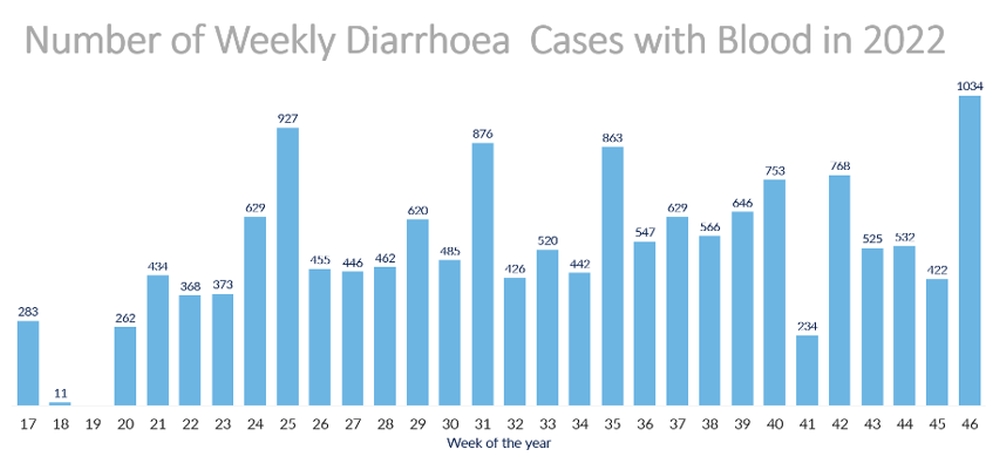

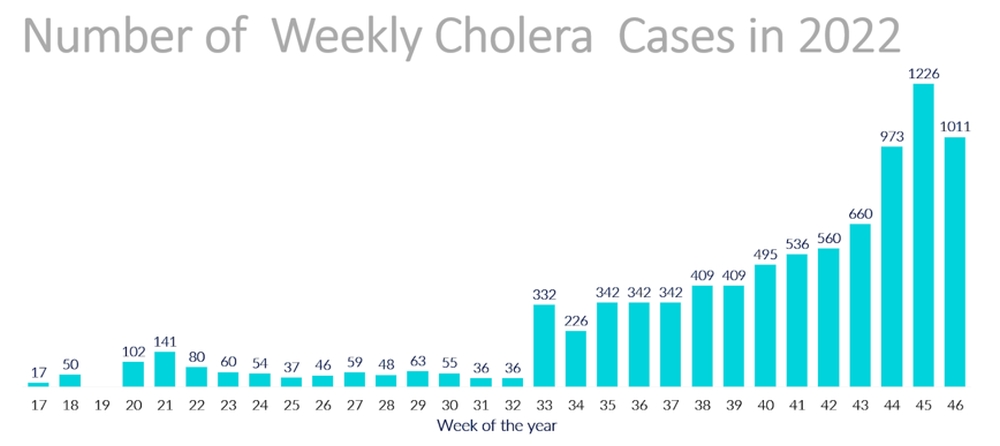

Foodborne diseases